Before diving into what scientific notation is and how to write it, let’s explore why we use it. Understanding its purpose will make learning the topic much more meaningful.

Have you ever tried writing out the mass of Earth? It’s about 5,972,400,000,000,000,000,000,000 kg, a number so long it almost makes your head spin. Now imagine going the other way and writing the mass of an electron: 0.000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, 901,938,371, 39 kg. Be honest, you probably gave up halfway through reading that.

In physics, many physical quantities, such as mass, charge, distance, or energy, vary from extremely large to incredibly small values. To make these values easier to write, compare, and calculate, physicists rely on scientific notation.

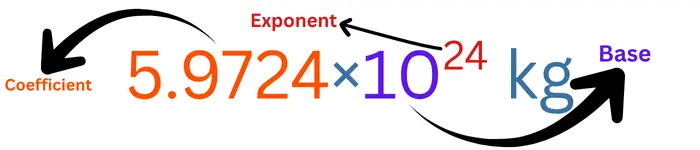

Instead of writing the full mass of Earth, they express it as \(5.9724\times10^{24}\;\mathrm{kg}\). Similarly, the mass of an electron is represented as \(9.109\;383\;713\;9\times10^{-31}\;\mathrm{kg}\), which keeps the number compact and manageable.

This article will explain what scientific notation is and show you how to do basic math with it.

What is Scientific Notation in Simple Words?

Any number written in the form \(\mathrm a\times10^{\mathrm n}\), where:

- a is the coefficient (having value \(1\leq a<10\) where a𝜖R (real number)). It means there should only be one non-zero digit to the left of the decimal point. It could be from 1 to 9.

- n is the exponent (having value \(-\infty<n<\infty\), where n is an integer). It means that the exponent can have any integer value, and it can be positive or negative.

- 10 is the base

is known as scientific notation. The value of exponent n is known as the order of magnitude.

The value of the mass of Earth in scientific notation is shown in the figure below, with its elements.

The order of magnitude of the mass of the Earth is 24.

The coefficient a is always greater than or equal to 1 and less than 10, so it is always positive. However, the number in scientific notation can be negative if a minus sign is placed in front of it.

In mathematics, scientific notation is also known as the standard form of decimal numbers. Also, in the UK and many other countries, it is often referred to as standard form or scientific form.

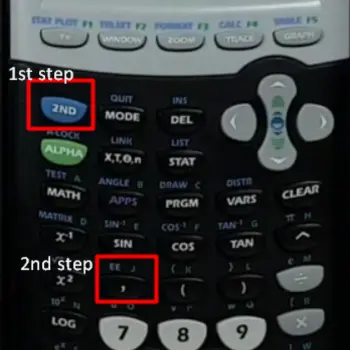

E in Scientific Notation – The Alternative to x10

Instead of writing x10, we can also write E (which means 10 to the power of).

So, \(\mathrm E=\times10\).

For example, the value 0.001 can be written in scientific form as \(1.00\times10^{-3}\) or 1.00E-3.

The E notation is often used in scientific and graphing calculators like the TI-84 Plus. In TI-84 plus, to write the number in scientific notation, you first write the coefficient and then instead of writing \(\times10\), you write E (by clicking “2nd” and then “,”). After writing E, you directly write the value of the exponent.

Rules to Avoid Mistakes

When working with scientific notation, especially in physics, it’s important to follow a few key rules to avoid errors.

Coefficient Range: As mentioned before, the coefficient is always greater than or equal to 1 and less than 10. So, there should only be one non-zero digit to the left of the decimal point.

Exponent is an Integer: Exponent would always be an integer value (….,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,….)

Exponent sign convention: If we move the decimal point from left to right (as in the case of 0.0023), the value of the exponent will be negative. If we move the point from right to left (as in the case of 29900), the value of the exponent will be positive.

Base is always 10: The base should always be 10. There shouldn’t be any other number used in place of it.

Precision of Coefficient: The number of digits in the coefficient shows how precise the measurement is. Don’t add extra zeros beyond the measured or known precision.

How to Convert Decimal Numbers into Scientific Form?

To write a decimal number into scientific notation might sound tricky, but it’s actually pretty simple once you know the steps. Think of it as repackaging a number so it’s easier to work with, especially when dealing with very large or very small values.

Here’s how to do it step by step:

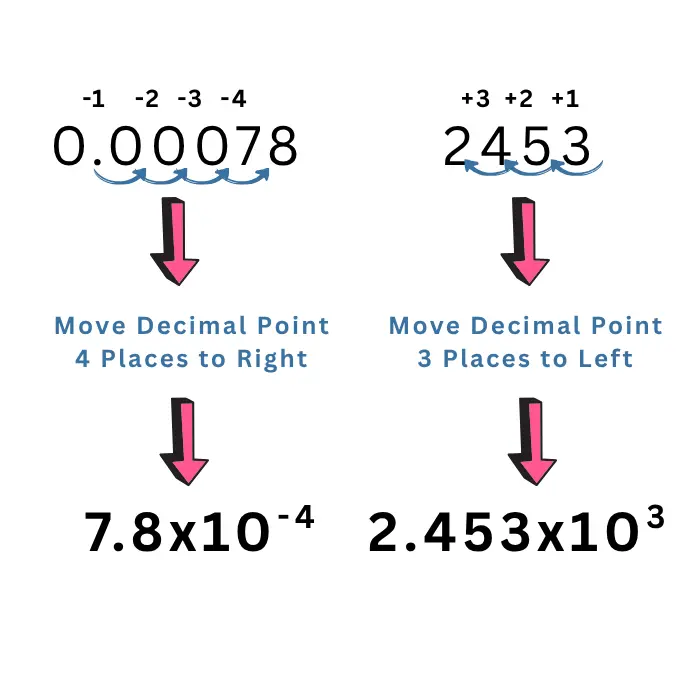

- Move the decimal point to the left or right until there is only one non-zero digit on the left of the decimal point.

- The number of places you moved the decimal determines the exponent of 10. Count the number of digits passed by the decimal point to put one non-zero digit on the left of the decimal point. That counting number would be the exponent of 10.

- If you move the decimal point from left to right, the sign with the exponent would be negative. For example, \(0.00078=7.8\times10^{-4}\). If you move the decimal point from right to left, the sign with the exponent would be positive. For example, \(2453=2.453\times10^3\).

And that’s it. With just these three steps, you can transform any ordinary decimal into scientific form. Let’s see some examples of it to better understand the concept.

Note: If a number does not show a decimal point, we assume it is at the end of the number. For example, in 2453, the decimal point is assumed to be immediately after the digit 3.

Scientific Notation Examples for Better Understanding

The table below shows some examples of converting numbers from their decimal form into scientific notation. It will help you to better understand the concept.

| Decimal Number | Scientific Notation with Base 10 | E-Notation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.00015 | \(1.5\times10^{-4}\) | 1.5E-4 |

| 0.000081 | \(8.1\times10^{-5}\) | 8.1E-5 |

| 0.00097 | \(9.7\times10^{-4}\) | 9.7E-4 |

| 0.00001 | \(1.00\times10^{-5}\) | 1.00E-5 |

| 1000000000 | \(1.00\times10^9\) | 1.00E9 |

| 673.5 | \(6.735\times10^2\) | 6.735E2 |

| -82704000 | \(-8.2704\times10^7\) | -8.2704E7 |

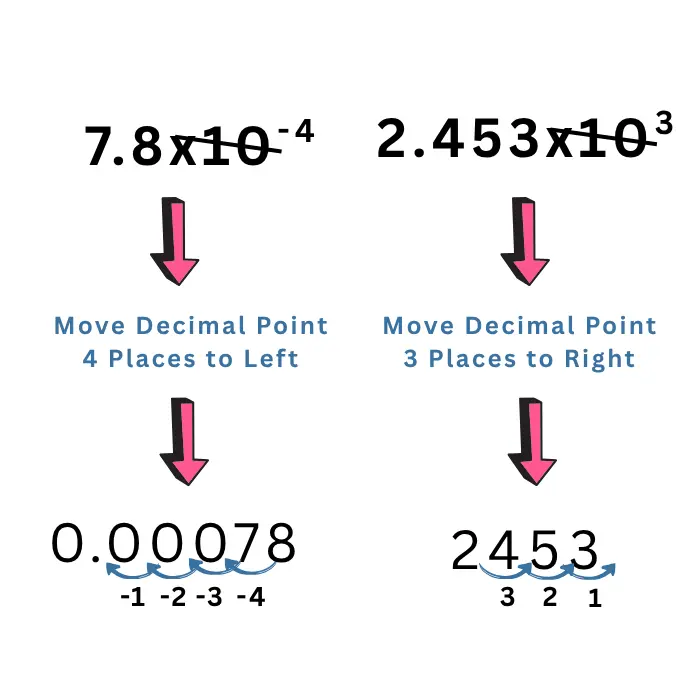

How to Rewrite a Scientific Notation Number in Decimal Format?

Now that you know how to write a number in scientific notation, let’s flip the process. Sometimes you’re given a value in scientific notation and asked to convert it into a decimal number.

Converting it back into a regular decimal number is just doing the opposite. Here’s how it works:

- The exponent on x10 tells you which direction and how far to move the decimal point in the coefficient (the number in front).

- If the exponent is negative, move the decimal point to the left as many places as the exponent shows. For example, \(7.8\times10^{-4}=0.00078\).

- If the exponent is positive, move the decimal point to the right as many places as the exponent shows. For example, \(2.453\times10^3=2453\)

- Once you’ve moved the decimal, you no longer need “×10^”. Remove it, and what’s left is your number in standard decimal form.

That’s it. You have converted the scientific notation into a decimal number.

How Calculations Work in Scientific Notation?

Now that you know what scientific notation is, let’s take it a step further. What if someone asks you to add two numbers written in scientific form? How would you do it? And what about subtraction, multiplication, or division?

In this section, you’ll learn how to perform each of these operations, with clear examples to help you understand them easily.

How to add and subtract scientific notation?

The rules for adding and subtracting numbers in scientific notation are the same, which is why we’ll cover them together.

Here is a step-by-step process to do this

- Look at the powers of base 10 for each number.

- If they’re different, rewrite one (or more) number(s) so all exponents are the same.

To increase an exponent by 1, you move the decimal point in the coefficient one place left and add 1 to the exponent.

To decrease an exponent by 1, move the decimal point one place right and subtract 1 from the exponent. - Keep the common ×10exponent and perform the arithmetic on the coefficients only.

- If the resulting coefficient is not between 1 and 10 (e.g., it’s 12.3 or 0.123), adjust the decimal and change the exponent accordingly so the coefficient is in [1,10).

- Write the final answer in proper scientific form with units if needed.

Let’s see how this works with an example. Suppose we have two masses:

\[3.14\times10^4\;\mathrm{kg}\]

\[1.2\times10^2\;\mathrm{kg}\]

If we want to add these two masses, we first need the exponents to be the same. Let’s adjust the second number to have an exponent of 4.

As mentioned in scientific notation rules, shifting the decimal point to the left increases the exponent positively. For example, to rewrite \(1.2\times10^2\;\mathrm{kg}\) with an exponent of 4, we move the decimal point two places to the left:

\[1.2\times10^2=0.012\times10^4\;\mathrm{kg}\]

Now that both numbers have the same exponent, we can add their coefficients:

\[3.14\times10^4\;\mathrm{kg}+0.012\times10^4\;\mathrm{kg}=(3.14+0.012)\times10^4\;\mathrm{kg}=3.15\times10^4\;\mathrm{kg}\]

Subtraction works the same way: adjust the exponents to match first, then subtract the coefficients.

In general form, we can write

\[z_0=a_0\times10^{n_0}\] \[z_1=a_1\times10^{n_1}\]

\(z_0\pm z_1=(a_0\pm a_1)\times10^n\) , where \(n=n_0=n_1\)

Also, to add two physical quantities, the units of them must be the same. You can’t add the mass of an object to its speed.

How to Multiply Scientific Notation?

When multiplying numbers in scientific notation, multiply their coefficients and add the exponents of base 10. If the final result is not in proper scientific form, convert it so that it is.

In general,

\[z_0=a_0\times10^{n_0}\] \[z_1=a_1\times10^{n_1}\]

\[z_0z_1=a_0a_1\times10^{n_0+n_1}\]

Let’s take the previous example of masses and multiply them

\[3.14\times10^4\;\mathrm{kg}\;\mathrm x\;1.2\times10^2\;\mathrm{kg}=(3.14\mathrm x1.2\;)\times10^{4+2}\;\mathrm{kg}^2=3.8\times10^6\;\mathrm{kg}^2\]

For multiplication, the units of both physical quantities don’t need to be the same. It could be the same or different.

How to Divide Scientific Notation?

Dividing numbers written in scientific form is just as easy as multiplying them, you simply handle the coefficients and exponents separately. Here’s how:

- Take the top number’s coefficient and divide it by the bottom number’s coefficient.

- For the powers of x10, subtract the exponent of the bottom number from the exponent of the top number.

- Make sure the final answer is in scientific notation. If it isn’t, adjust it accordingly.

In general form, it is written as

\[z_0=a_0\times10^{n_0}\] \[z_1=a_1\times10^{n_1}\]

\[z_0/z_1=(a_0/a_1)\times10^{n_0-n_1}\]

Like multiplication, the units of both scientific forms need not be the same. For example,

\[d=2\times10^5\;\mathrm m,\;t=3\times10^3\;\mathrm s\]

\[d/t=(2/3)\times10^{5-3}\;\mathrm m/\mathrm s=0.7\;\times10^2\;\mathrm m/\mathrm s\]

The final result of all the above values is rounded and expressed according to the rules of significant figures.